Cobalt mining on the African Copperbelt is a well known human rights crisis for many reasons. A new study on foetal blood shows its health effects may now materialise in Congolese infants before they are even born. By Charlotte Leeds.

Cobalt is a by-product of the Cobalt-Copper Ore mined on the African Copperbelt. It is a highly prized element, due to its application within the lithium-ion batteries of mobiles, laptops, and electric vehicles [1]. Cobalt mining on the African Copperbelt is a major human rights crisis with significant health impacts, causing tumours, respiratory issues, and metabolic disorders to name a few. Now, it has been found that these effects may be passed down to the next generation, before they are even born.

A previous study on cobalt transfer from mother to foetus found no significant difference between maternal and foetal blood, concluding that cobalt does not cross the placenta, adding that umbilical blood had a 60% lower cobalt concentration than maternal blood. However, a more recent paper contradicts this. It was found that babies born to mothers living in the city of Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have an increased blood cobalt concentration, higher than their mothers. The mothers in this study were not working in the cobalt mines but lived in communities where it is prevalent - many with partners in the industry. The discrepancies between studies were likely due to the source of metal exposure studied. Whilst the previous paper studied cobalt exposure in patients with metal-on-metal hip devices, the recent paper was based on exposure through cobalt mining[2].

In the recent paper, samples of umbilical cord blood, placental tissue with maternal venous blood, and urine were taken to analyse the concentrations of toxic elements such as arsenic, uranium, and cobalt. Researchers found the concentrations of cobalt in these samples were significantly higher than in other non-occupationally exposed adults. The most striking findings in the paper were that cobalt concentrations were 40% higher in the newborn’s blood compared to their mother’s, indicating active uptake by the foetus in utero.

Despite not working in cobalt-exposed environments themselves, 22% of the mothers within the study exceeded The Biological Exposure Index’s concentration limit of cobalt in occupational settings, set at 15ug/L urine. The wider implications that unregulated (and often regulated) mining has on the health of a community are extremely concerning, exacerbating the current human rights crisis in the DRC.

Cobalt is integral for the synthesis of cobalamin - a metal coenzyme that plays a role in a number of biological functions. More commonly known as vitamin B12, cobalamin metabolises fats, and carbohydrates, stimulates DNA synthesis, and is associated with normal brain and nervous system functions [3].

Due to its use in hip implants, research into the effects of over-exposure to cobalt has already begun. Within the mining industry, cobalt can be easily absorbed through inhalation and skin contact [4]. Effects seen in studies include a range of cardiovascular and endocrine deficits along with neurological impairments. As newborns are more susceptible to the impacts of toxic elements than their mothers, they may be born with birth defects.

Beyond cobalt exposure itself, the process of mining on the African Copperbelt is accompanied by a myriad of other health and safety violations. There have been about 10-15,000 tunnels dug by hand without any support structure, causing constant collapses that bury miners alive [5]. Even if the tunnels hold, that stagnant water that many miners spend their work lives digging through, often spreads diseases, toxins, and cancer-causing particles [6].The cobalt mining industry is composed of industrial and artisanal mining, the latter of which is often illegal, dangerous, and unregulated. However, the commercial outputs of both are extremely intertwined and it is almost impossible to separate which sector they came from. [7]. There is a long history of governmental issues within the African Copperbelt and the power global big tech holds over the resources there is a root problem.

A brief improvement period was seen due to The Mutoshi Formalisation Experiment in 2018, involving bringing in excavation machines to replace hand-digging the mines. Additionally, uniforms and ID cards were introduced to better regulate workers and access to the mines, in part attempting to combat child slavery. Unfortunately, this project came to an end due to the COVID-19 pandemic, causing an increase in deaths and bringing a level of fear back to the mining community [4]. A more detailed review along with the information on the ongoing human rights crisis in The African Copperbelt can be found in Siddharth Kara’s book ‘Cobalt Red’. To prevent further health impacts on the next generation of Congolese children, societal changes would have to take place within the DRC and worldwide. Health impacts of cobalt should not be addressed in a vacuum, without challenging the root causes of governmental issues and technological demands.

Article written by Charlotte Leeds

References:

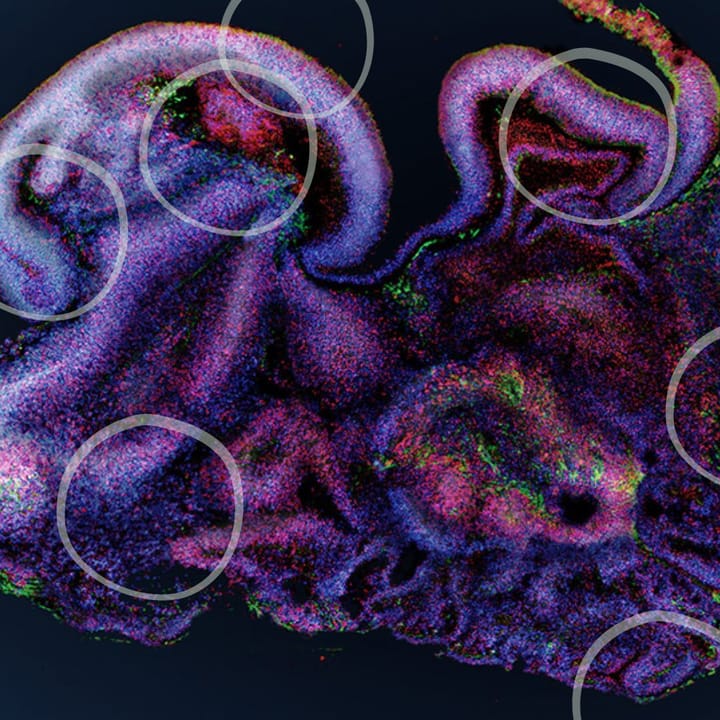

Cover Image: V. Rajavat, UCL Science Magazine Graphic Designer

- Cobalt Institute. Cobalt Market Report. 2020

- Kayembe-Kitenge T, Nkulu CLB, Musanzayi SM, Kasole TL, Ngombe LK, Obadia PM et al. Transplacental transfer of cobalt: Evidence from a study of mothers and their neonates in the African Copperbelt. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2023;80

- Guo M, Chen Y. Coenzyme cobalamin: biosynthesis, overproduction and its application in dehalogenation—a review. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology. 2018; 17: (259–284)

- Wahlqvist F, Bryngelsson I-L, Westberg H, Vihlborg P, Andersson L, Ren X. Dermal and inhalable cobalt exposure- Uptake of cobalt for workers at Swedish hard metal plants. PloS One. 2020; 15(8)

- Gross T. How ‘modern-day slavery’ in the Congo powers the rechargeable battery economy. NPR. FRESH AIR. 2023

- Baumann-Pauly D. Cobalt Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Addressing Root Causes of Human Rights Abuses. NYU, Center for Business and Human rights. 2023

- Katz-Lavigne S. Is artisanal mining really worse than industrial mining? Land and Climate Review. 2023